How Wikidata is Coding for Humanity

Lydia Pintscher explains how this little-known project powers Wikipedia, AI tools, and civic tech around the globe.

For several years now, I’ve been intrigued by Wikidata, the structured knowledge base that underpins Wikipedia and many other free knowledge projects. I’d heard about it at Wikimedia events, and even enjoyed a bit of Wikidata cake to celebrate the project's birthday. Still, the practical use cases always felt a bit abstract. Wikidata is the data-driven dimension of Wikipedia—I understood that—but what does that actually mean in real-world terms?

So I was glad to have a short conversation with Lydia Pintscher, Portfolio Lead for Wikidata at Wikimedia Deutschland, to explore that very question. Lydia walked me through how Wikidata works, what makes it different from Wikipedia, and why it matters far far beyond the immediate Wikipedia community. I’m happy to share our discussion with you.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Stephen Harrison: Hello, Lydia. Could I ask you to please introduce yourself?

Lydia Pintscher: Hi everyone. I’m Lydia and I’m the portfolio lead of Wikidata and I work for Wikimedia Deutschland.

Harrison: Back in 2019, I attended Wikimania, the annual user conference for Wikipedia [and the related free knowledge projects]. This was the year it was hosted in Stockholm. And I remember first of all the enthusiasm at the event, and also that there was a large cohort of people from Germany who were involved with Wikimedia Deutschland. Can you tell us more about that organization?

Pintscher: Next to the Wikimedia Foundation, it’s the biggest organization in the Wikimedia movement and the first official chapter. It’s been around for a long time now supporting the German language Wikipedia. And it’s mainly responsible for Wikidata, which is Wikimedia’s knowledge graph.

Harrison: Tell me more about Wikidata and how it’s different from Wikipedia.

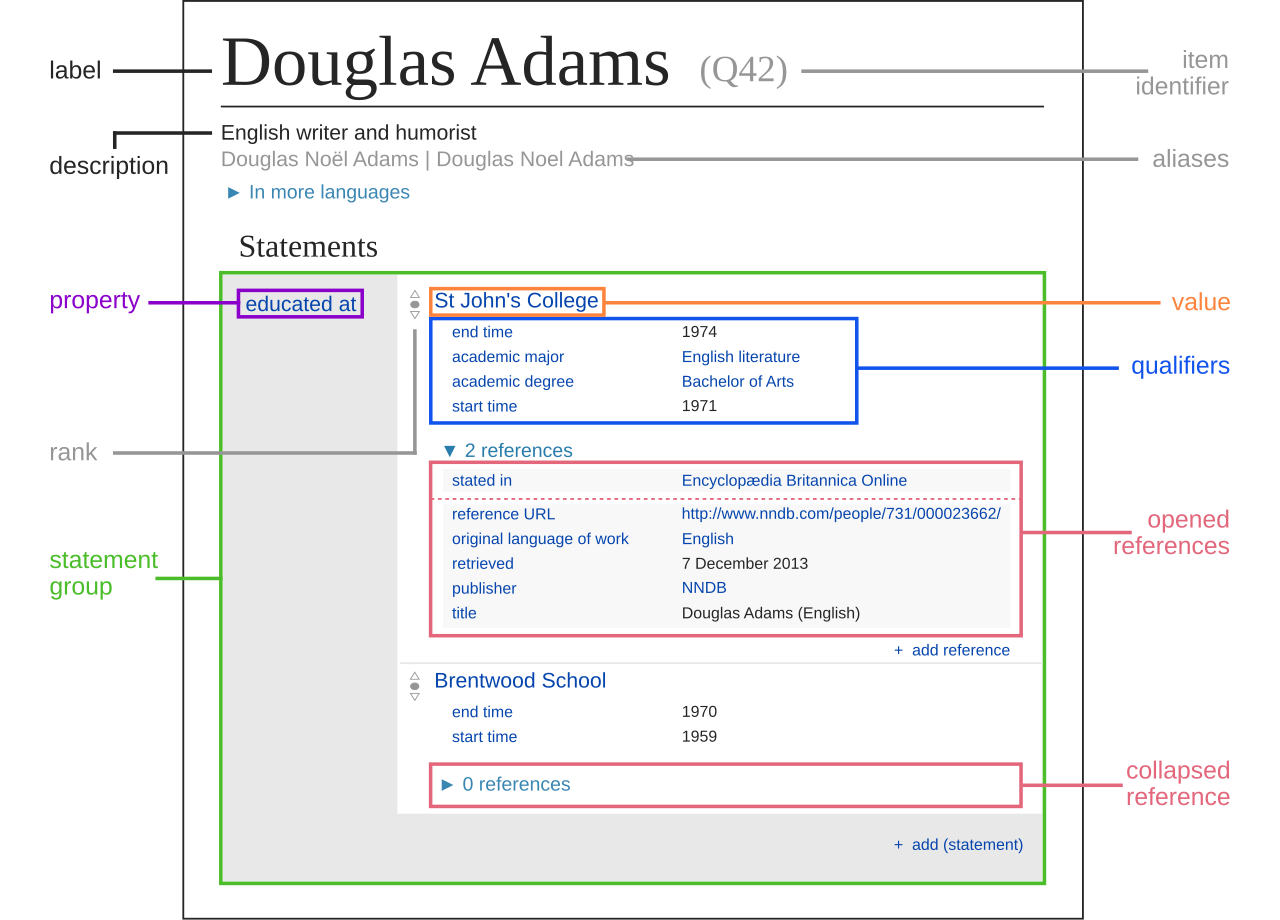

Pintscher: So Wikidata is an open project where people contribute similar to Wikipedia, but instead of text, we are talking about data. For example, people are collecting data such as the number of inhabitants of a country, or the current head of government for a country. The Wikidata entry on a person might state their profession or their data of birth. And all of that is stored in Wikidata, available as a resource for anyone to use, and contribute to as they do with Wikipedia.

Harrison: My mental image for Wikidata is something like this. You have a Wikidata item for London and that includes the population of the city. And then that data can flow out of Wikidata and into the different language editions of Wikipedia, into English Wikipedia, German Wikipedia, Spanish Wikipedia, and so forth. That way there can be some sort of consistency.

Pintscher: That was the original idea that we started with in 2012. There were about 300 different language editions of Wikipedia. [Note: Each language of Wikipedia is separate and is managed by its own community of volunteer editors.] Some editions were very large with lots of editors taking care of that content, writing articles and maintaining the information. And there were also very small Wikipedias where there were just a handful of people involved.

Let’s say that someone is elected to the role of mayor of Berlin. That would be a lot of work to update it in the 300 different language editions of Wikipedia, and there may not be enough people on the smaller wikis to make that change. It’s also not very meaningful work to make that change over and over. So we thought: why not just have one place where that gets updated and then the other Wikipedia editions can pull from there? That’s basically how Wikidata started.

Harrison: Have you found that the contributors to Wikidata overlap with the editors of Wikipedia?

Pintscher: Yes, there’s a lot of overlap. But there are also people who have found their place in the Wikimedia movement through Wikidata specifically. They preferred to work with data and were not so excited about writing articles.

Harrison: When I was first looking into Wikidata, I thought that you had to be a programmer to contribute to the project. I found that, actually, the properties in the structured data were pretty easy to understand. You can just point at and edit the data fields.

Pintscher: Exactly. Sometimes it’s much easier to contribute to Wikidata because you’re making those small contributions. As opposed to writing something longer, you can just add a data point. You’re updating the mayor of a city, you’re adding a rating for your new favorite movie… Whatever floats your boat.

Harrison: I understand there are a lot of different use cases for Wikidata—even several that extend far beyond the world of wikis.

Pintscher: Yes, the data from Wikidata is spreading our knowledge even further. One example that I find really cool in the public policy sector is a project called Govdirectory, which was started by two Wikidata editors. Govdirectory provides an easy way for people to figure out how they can contact their government for a specific topic that they care about. For example, it would provide an easy way to find an official government social media account. You could find who in your government is responsible for an environmental matter. Govdirectory is based on the information in Wikidata about how the government of a country is structured and the various contact points.

Harrison: For a project like Govdirectory, does the Wikidata volunteer manually put that information into Wikidata?

Pintscher: Wikidata contributors do the work. [laughs] Some of its handcrafting. But there are a lot of tools like “Mix’nmatch” to support the editing. With Mix’n’match, you can match a Wikidata entry to an existing catalog. There are also mass editing tools that can allow the user to bring a recent governmental report into Wikidata.

Harrison: I would expect that in some countries, the information for contacting government officials may be more easily accessible, but it would be less so in others.

Pintscher: That’s right. We have a project called Every Politician that has a registry of data for all the politicians for all the countries in the world. Because this is something journalists and activists need. It was so important to have an up-to-date list. We’ve done a lot of work to ensure that this pipeline of data is open and accessible to people.

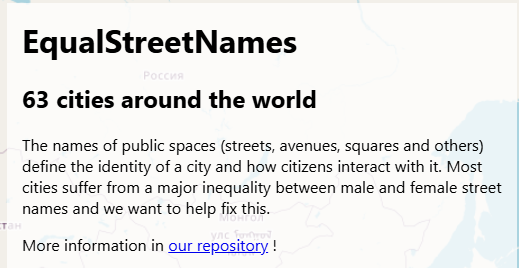

Harrison: Your Wikidata team also told me about this project called EqualStreetNames.

Pintscher: Yes, the theory behind EqualStreetNames was to bring attention to the fact that when we name streets, we very often name them after famous men. There’s a lot of reasons for that, and it’s something we wanted to bring attention to. So if you go to the EqualStreetNames project, you can get a map for your city based on the data found in Wikidata. Then you can get a colored map of how many of your city streets are named on men versus women. Then somebody did an experiment on top of that, which was to see if they could travel only following streets that were named after women.

Harrison: Oh wow. Was that even possible? I mean, did it even work?

Pintscher: I wouldn’t want to travel like that, let’s say. It would be very difficult.

Harrison: It would be challenging to lug your books around like that. And I heard that Wikidata has a project that’s specifically dedicated to physical books?

Pintscher: Yes, there’s the book sharing network Inventaire. The idea is to support the sharing economy for books by registering which books you have. Without Wikidata, building something like this would be very difficult, because you’d have to start from scratch in putting in the data points: the author, the genre, the publisher, and so forth. But with Wikidata, you can have the system pull up an author, say, Douglas Adams, and it will bring in a blurb about him and his author photo.

Harrison: Funny that you mention a sci-fi author because I was just thinking about how we haven’t yet talked about AI yet and that seems like a miss on my part. From what I’ve read, the AI apps like ChatGPT pull a lot of their information from Wikidata.

Pintscher: Since the beginning of Wikidata, we’ve wanted it to be both human and machine readable. The data should be readable to a human, but it might reach a wider audience if it is also readable and usable by a machine.

Harrison: What language is the machine using to read Wikidata? Is it different from the human-readable text?

Pintscher: All of Wikidata’s data is published following linked open data standards. So, for example, you can get an RDF [raw data file] export, which may be easier for certain tools to use. Or you can get the data in a JSON export and use that to build, whichever type you need.

Harrison: Seems like Wikidata was set up in a very smart way since the beginning! Can you speak about any challenges that Wikidata is having as a project?

Pintscher: I would say one challenge is that Wikidata is sort of a background project. It’s seen as the data backbone to Wikipedia and other projects, but it’s not always in people’s faces. People don’t necessarily know where the data is coming from. So we’ve started a campaign to encourage the organizations that are building applications with Wikidata to name Wikidata as a source for the data that they’re presenting.

Another issue is scalability. Right now Wikidata has about 116 million entries but only about 25,000 people who contribute every month. That’s a lot of data to keep up to date!

Harrison: If you had to make a pitch for why someone should volunteer their time to Wikidata, what would you say?

Pintscher: First of all, it’s an amazing project with an amazing community, of course. But more seriously, it is the source of so much of the technical infrastructure that you use everyday without you even being aware of it. Your contributions to Wikidata spread so much further than a lot of contributions you could make in other places. So if you’re looking to really have an impact, go to the source.

Thanks to Lydia Pintscher for her insights. You can read more about Wikidata at its intro page.